Pornography is the pandemic

2020.12.13 // BROOKLYN //

Hello.

This is Friday Letters, on Sunday.

I don’t know how nice it was out in Atlanta yesterday (it’s a climate-changed high fifties here), when Lisa Hagen, a radio reporter with WABE (Atlanta’s NPR station), captured this moment at a pro-Trump rally. As has been the case across the country, these rally/revival/protests attract a broad spectrum of what we would have called, one hundred years ago, social purity campaigners:

For anyone (me, too) with a fresh memory of watching any of the 1992 RNC speeches by the Pats Robertson and Buchanan… or ever bought a CD with a “PARENTAL ADVISORY EXPLICIT CONTENT” label… or cringed at a Nightline correspondent blandly cataloguing a music video’s “nudity, suggestions of bisexuality, sadomasochism, multiple partners”—before showing it—thirty years ago this month, which means that is also what was obsessing broadcast media in the few weeks before the United States invaded Iraq… the culture war can, by now, feel like a cold one.

Until a week or so ago, I would have said that, too.

NEW WORK //

“Nick Kristof and the Holy War on Pornhub” / The New Republic (December 10, 2020)

“In my work with Exodus Cry, I am daily confronted with the horrors of a world ravaged by the degradation of women and children,” writes the group’s founder Benjamin Nolot, in the foreword to a book called Babylon: The Resurgence of History’s Most Infamous City, published in 2009 by the evangelical ministry International House of Prayer Kansas City, or IHOPKC. “An unprecedented movement of slavery and sexual exploitation is rising in the vacuum of moral decay. As we examine the emergence of Babylon throughout history, it becomes clear that we must see the increase of human trafficking as the tip of a much larger historic iceberg.” For Nolot, human trafficking is a sign of the end times, “one of several troubling trends that will converge in the birth of the next world empire: harlot Babylon.” To fight those who aid and abet trafficking—as Exodus Cry claims that Pornhub does—is to wage holy war.

There is no question that Pornhub sits at the crux of two bad ideas: a race-to-the-bottom gig economy and a tech-determinist business model that values stickiness and seamlessness over content moderation. But the abuses that all this enables are not signs of the end times; to confront them with a religious crusade is not only useless but dangerous. Pornhub can continue business as usual so long as it can say its loudest critics are just pissed-off fundamentalists. Stuck in the predictable pushback to anti-porn “puritans,” the possibilities for challenging Pornhub’s business model—and the working conditions and the exploitation it enables—could be lost.

My online feature on Kristof’s new comrades, an anti-porn group, with longstanding ties to a Christian dominionist church, and led by a man who has written that sex trafficking portends the end times and the literal return of Babylon.*

Longtime readers know that there is no love lost between me and New York Times opinion columnist Nick Kristof. But even I have my limits (I once turned down the offer to write a whole book on him because, who wants to read that if I barely want to do the reading to write it?) and I know exactly what to expect from 1200 words of him expressing his Nice Guy’s Burden. He hates rape. He writes a lot about it. He doesn’t hate sex. He often uses pain to arouse a reader’s conscience.

Now Kristof has discovered online pornography. (Before this month, of 1249 Kristof columns posted online, six returned results for “porn,” and those were about Trump.) Not coincidentally, an already-aggressive online campaign called “Traffickinghub,” targeting the website Pornhub, was ramping up. This was perfect Kristof fodder: a website that is allegedly conspiring in sex trafficking women and even girls? It is not an exaggeration to say this is a beat he pioneered.

As soon as I saw the headline, the byline, and the art (a close-up portrait of a young woman looking off into the distance), it was obvious to me that this was, in addition to a coup for Kristof, another stage of the Traffickinghub campaign. But I was still pretty amazed to read—or not-read—that the group behind that campaign didn’t get a single mention.

So I corrected that.

Just over the last few months, the line between legitimate-seeming anti-trafficking groups and QAnon supporters has grown thinner. I started paying attention when stories started popping up (by reporters on the disinfo/extermist beat) about QAnon people getting in the way of anti-trafficking groups’ work, like clogging up hotlines and generating bogus tips. But the problem was, too many of those groups were already prone to the kind of sensationalizing and exaggerated claims that could be a draw for QAnon. Both made movement-building appeals on things like stolen innocence or sex slavery.

When QAnon supporters themselves mobilized over the summer under the toned-down banner of “Save the Children,” local news covered the resulting rallies just like any other anti-trafficking group and their events. One conclusion you could draw from this is that QAnon was usurping the legitimate anti-trafficking movement. But the truer one is that QAnon was successful in actually mobilizing people, over multiple weekends in dozens of cities in the U.S. and in Europe, around the cause of saving children from sex slavery, something that the contemporary anti-trafficking movement has failed to do in its two decades of existence.

I had been only sort of joking a few weeks ago, about what Kristof was going to do with his new constituency. So to see his coverage of a sexual purity campaign pitched as his own Spotlight moment, while knowing it was made possible by a far right group successfully rebranding itself as something more palatable, to me it feels like just another confluence of the interests and influence that powered the “Save the Children” mobilization. The overlap, too, between “Save the Children” and “Stop the Steal” is not small. And the same, possibly, is true for the “reopen” anti-mask rallies and protests.

I think there could be something new coming together, in the cracks between what the anti-trafficking movement promised and what it accomplished, along with the disappointment amongst the QAnon supporters who didn’t get the president they were promised, either. A comedown is just another way of saying you’re looking for another high. Another story to live inside of, where you are the hero again, and the fallen world, well—fuck it.

After the last week, I’m no longer unwilling to call such a thing a “culture war.” It’s more likely that “culture war” is going to feel insufficient to describe whatever it is. And it might make the Pats seem like they aimed way too low.

READING, ETC. //

- This blockbuster dismantling of the anti-trafficking group Operation Underground Railroad at VICE World News this week, from Anna Merlan and Tim Marchman.

- This is more a note-to-self to-read, after an overload of too-small debates about content moderation: “Platforms don’t exist.”

- Sophie Lewis, on a too-small feminism, too.

- If you need a creative break, sign up here to create some holiday cards you print and can even color them in yourself for folks in jails and prisons. (If you own a printer and keep stamps on hand, you are pretty much obligated to do this.) Sign up with Black and Pink to be assigned fifteen people who need a holiday greeting.

If you need a spiritual and mental break (not like that): the music supervisor on Party Girl (1995) put this supersized mixtape together (soundtrack + “after hours”)

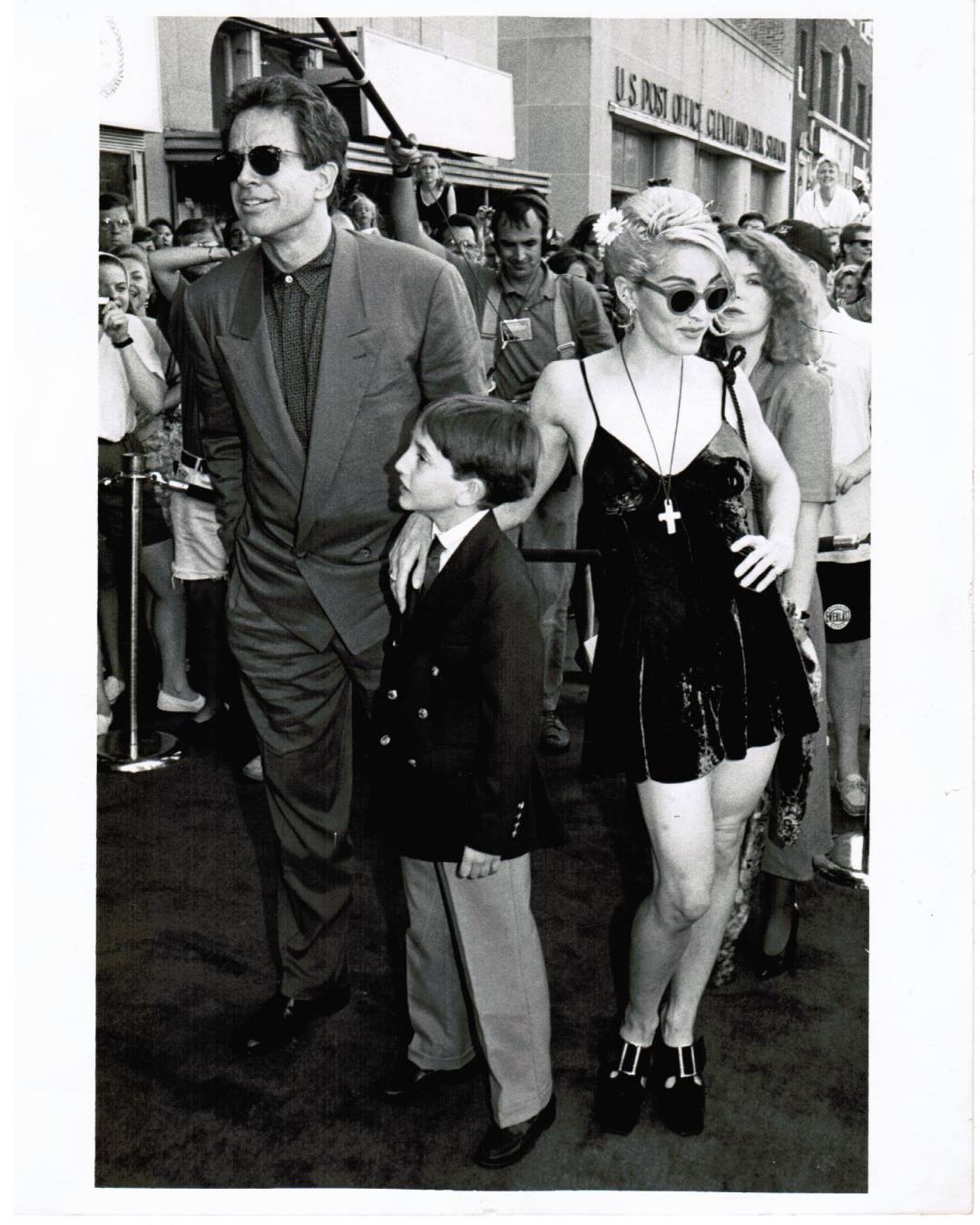

And, relatedly, an essay I will probably never write, so, go for it: why whatever art directors of the early 1990s thought the 1930s looked like had such an outsized influence (photo: around that time Madonna got Warren Beatty to… sing). I wouldn’t call this period 1990s-does-1930s. Maybe Munster Moderne?

BACKMATTER //

“QAnon Is Using the Anti-Trafficking Movement’s Conspiracy Playbook” / The New Republic (August 19, 2020)

Seven years ago, as OUR tells its origins story, Tim Ballard left his job as an agent in the Department of Homeland Security to launch a group where he could do the same work, unbound by the government. When I met him at a junket in lower Manhattan five years ago, he implored us assembled members of the media to be like modern-day “Harriet Beecher Stowes,” telling the stories of the children Ballard and his undercover operatives say they liberated from child sex trafficking. It is very modern: the abolitionists he styles himself after didn’t have 501c3s. In 2019, “Operation Underground Railroad Inc.” brought in more than $22 million, and he served as a White House anti-trafficking advisor appointed by President Trump. Flourishing as they are in the Trump era, it is hard to say if OUR has gained respectability despite their vigilantism or because of it.

My story from the summer, as “Save the Children” was just getting off the ground, and the boost it got from the same group VICE dug into.

STATION IDENTIFICATION //

This is Friday Letters, by Melissa Gira Grant (me).

But it’s Sunday. Thanks for reading again.

x

MGG

* As a result of the Pornhub debacle, I’ve had to think and write and argue more about porn this past week than I have, probably, since I thought it would be so transgressive (THANKS MADGE) to make some. I’m pretty sure 99 percent of the men who now want to have arguments on the internet with me about porn probably don’t know that? It wasn’t that long ago when someone pointed out to me that I didn’t seem bothered by having posed nude for photos he’d post online the same week I had my first story come out at a biggish news and politics site. Nudes are always one click away, who cares if they are mine, etc. etc. and yet, I’m not mad that enough time has passed that it might as well be someone else. But it is not.

//melissagiragrant.com

// 00088

Member discussion